Let's Get Hei-Pi: A Review of Black-faced Spoonbill Conservation Efforts in Taiwan - Part 1

by Scott Pursner

Part One of a Two Part Series

Photo: Philip Kuo

The Black-faced Spoonbill (Platalea minor), whose global population has risen from a known 288 in 1990 to over 5,000 this year, is one of Asia's great conservation successes. This endangered migratory waterbird endemic to East Asia has not just become iconic in countries along the East Asian-Australasian Flyway, but has won over the hearts of enthusiasts and the public around the world. Its conservation success relied on the power of partnership and cooperation at both the local and international level. Taiwan, which sees over half the global wintering population and where it is affectionately known as “Hei-Pi” (since the “hei” and “pi” of its Chinese name sound like “happy”), made outsized contributions to that success. Here we look at that story.

Part 1: Early Days

It started with a letter.

In November of 1988, Mr. Lin Chih-cheng, a fertilizer company owner in central Taiwan's Miaoli County, received a letter from Mr. Peter Kennerly of the International Council for Bird Preservation in Hong Kong. It asked Mr. Lin if he could provide any historical information on the Black-faced Spoonbill, at the time a little-known species he was writing an article on for the Hong Kong Bird Report. According to Dr. Woei-Horng Fang, president of Taiwan's largest bird conservation organization, the Taiwan Wild Bird Federation (TWBF), Lin didn't know what to do with the letter since he was just a business owner with great interest in international topics. So, he brought it to the attention of Mr. Mei-Hua Tsou, Chief of Data for the Wild Bird Society of Taipei (WBST).

Fang explained that the WBST was the bird society with the best capacity to handle such an inquiry at the time since the TWBF had only been established earlier that year. After looking into the matter, Tsou reported to Kennerly that between 1985 and 1988, 40 birds had been recorded in Taiwan. This was corroborated in a paper presented by Dr. Lucia Liu Severinghaus, one of Taiwan's top ornithologists, at an International Council for Bird Preservation meeting in Bangkok in 1989.

In January of that same year, Tsao travelled with some birders to Zengwen Estuary in southwestern Taiwan's Tainan, where local birders claimed there was a wintering population of 120 to 130 birds. In 1990, the TWBF wrote to Kennerly to say that during surveys for the 1989-1990 Asian Waterfowl Census, 145 Black-faced Spoonbills had been counted in Tainan.

Kennerly would publish these population findings in a 1990 report, which also revealed that there were just 288 of the unique waterbirds between Taiwan, Vietnam, Hong Kong, China, South Korea, and Japan. Taiwan had 52% of the global wintering population of this critically endangered population. Locally, people were confronted with having the largest population of a species that until then hadn't been on the radar.

The Black-faced Spoonbill was first recorded in northern Taiwan's Tamsui in 1864. Then during the Japanese occupation of Taiwan (1895-1945), correspondence between famous ornithologists Tetsukichi Kazano and Yoshimaro Yamashina showed that there were around 50 Black-faced Spoonbills around Tainan's Anping District, which lies south of the Zengwen Estuary. However, prior to the the mid-1980s, these were the only official records.

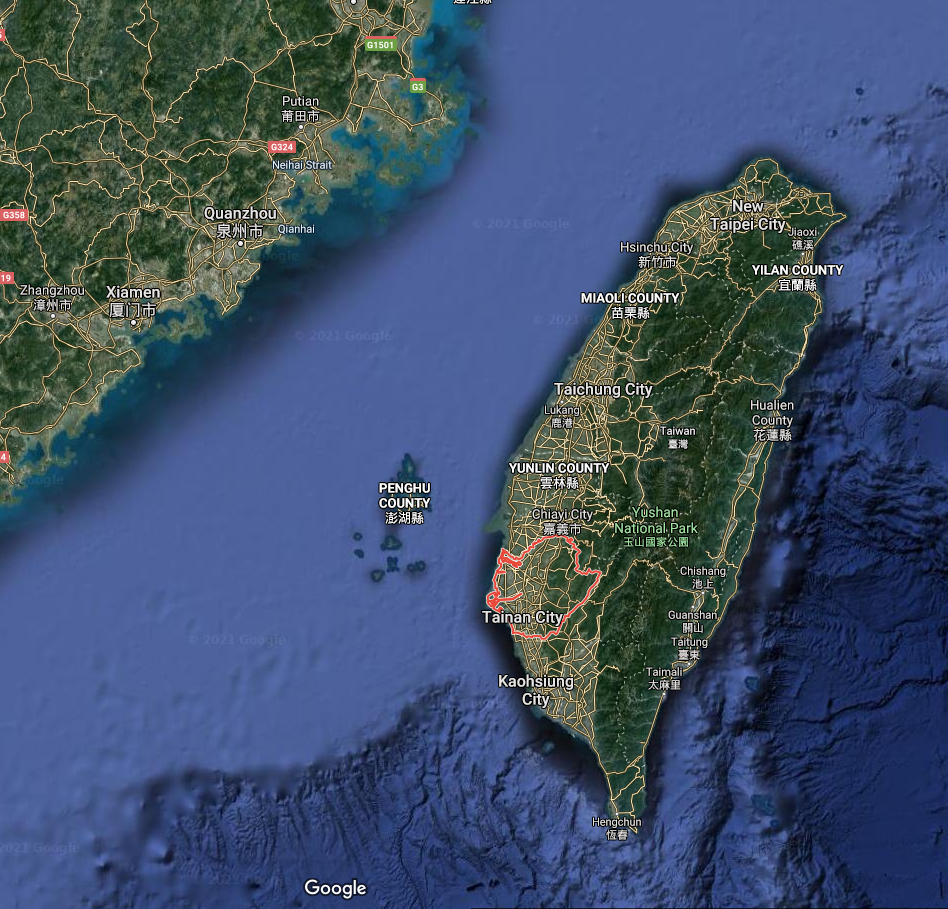

Taiwan with Tainan highlighted (Google)

Tainan and major areas for Black-faced Spoonbills

In the beginning, the major habitat was comprised of Chiku, north of the Zengwen estuary, which was part of Tainan County until its merger with Tainan City in 2010 and Sicao, north of the Zengwen estuary and traditionally a part of Tainan City. For Philip Kuo, former president of both the Wild Bird Society of Tainan and the TWBF, this habitat was key to preserving the species. Tainan, as a low area, was perfect for salt pans and fish ponds. As he put it, "Generally, the local economy of southwest coast revolved around aquaculture fisheries.”

Traditionally, the ponds for raising milkfish would go unused from October to April, and the water levels would slowly be allowed to decrease naturally. These areas are rich in non-target fish species and crustaceans, making them the perfect spot for waders that need around 10 cm of water for optimal foraging. This aquaculture practice had also been deeply engrained in Tainan’s tradition, with the Dutch having introduced this method to locals when they colonized the area in the 1600s.

A native of Tainan, Kuo said that in the late 1980s, awareness of the spoonbills extended only to some local photographers and birders. "Back then [in the late 1980s] there wasn’t even a bird society here. You only had them in Taipei, Taichung, and Kaohsiung. I belonged to the one in Kaohsiung until there was one here in Tainan.”

Yet once it was discovered that Tainan held the bulk of wintering Black-faced Spoonbills, the area previously known for its salt pans was on everyone's mind. Kuo explained, "The area was all salt pans and fish ponds and people didn't really think much about the ecological significance. But then the Kennerly report came out. And back then, they really wanted to develop these areas.”

As part of Taiwan's economic miracle of the late 20th century, both Sicao and Chiku were being threatened by industrial development plans.

After the Kennerly paper, all eyes were on Taiwan as there was more known about the wintering than the breeding grounds at that point. Government and conservationists scrambled to learn more about this relatively unknown species, which overnight went from data deficient to critically endangered internationally.

In one of the first steps, the central government's Council of Agriculture asked Professor Ying Wang, one of Taiwan's premiere wildlife researchers and a member of the COA's Wildlife Conservation Committee, to survey and monitor the birds and their behavior. Surveys began in 1991 and back then took place every week or two weeks depending on the volunteers available and interest.

As Wang put it, "the first five years were hard. We relied on a participant network and surveyed at night, which is when the birds are active. We also didn't have any of today's modern technology, such as night scopes or telemetry.”

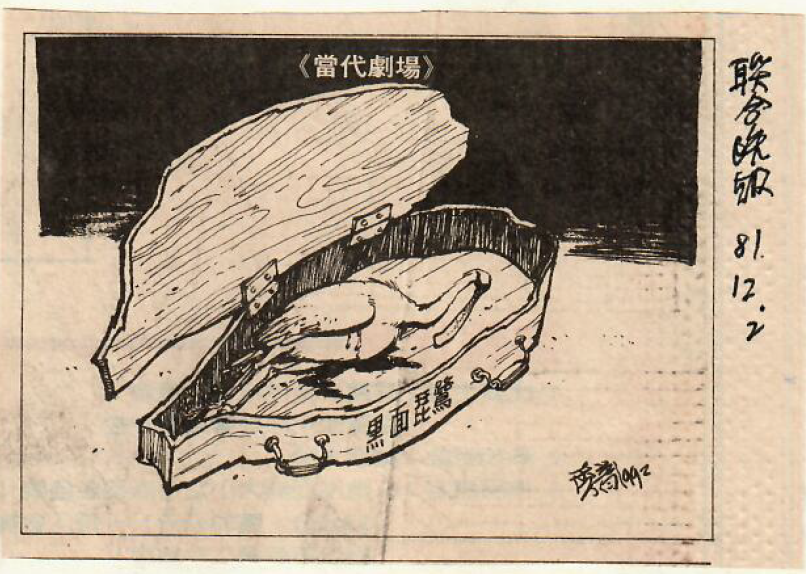

Political cartoon from the United Daily News Dec. 2, 1992 (Source: TWBF Archives)

Meanwhile, in September of the same year, the local government submitted applications to the central government to redevelop the area for industrial use. A science and industrial park was proposed Sicao and an industrial park for Chiku.

It was in 1992 that Black-faced Spoonbill conservation efforts in Taiwan truly took off. By this time, the TWBF was better established and had contacted the Wild Bird Society of Japan to ask for their advice on creating wildlife conservation areas while also facilitating development. The WBSJ provided materials for their Taiwanese counterparts to consider.

Meanwhile, locals in Tainan, many of whom surveyed with Prof. Wang, decided it was time to create a unified voice for Tainan's birds. In May of 1992, the Wild Bird Society of Tainan was established. Their initial goal was to help monitor and protect Tainan's birds as well as represent ecological concerns to businesses during development planning.

According to Kuo, they did this by serving as local nature-lovers who could talk with government and industry about proposed development projects. This information was also extremely important when the government was doing Environmental Impact Assessments and feasibility studies for future projects. If there were Spoonbills there, the WBS Tainan would try and explain that a different area should be selected for development. This could have been a hard sell but their case was bolstered by the COA's Forestry Bureau declaring the Black-faced Spoonbill as endangered and protected under the country's Wildlife Conservation Act in 1992. It was the first migratory species to be added to the list and this afforded it protections under the law including making it illegal to kill the birds.

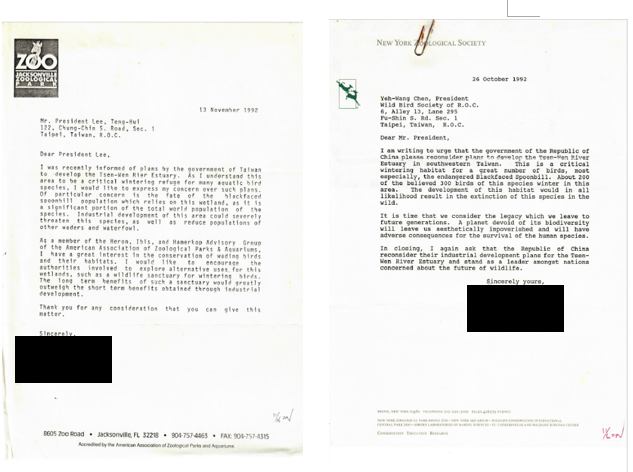

Another action taken was a letter-writing campaign. Utilizing known scientific and conservation networks, the TWBF asked friends from around the world to send messages to local- and national-level officials asking them to save the Black-faced Spoonbill. Messages poured in from across the globe telling the government not to develop this critical habitat for the Black-faced Spoonbill. Dr. Severinghaus noted, "We had people in California writing letters about how precious the Black-faced Spoonbill is. They had maybe never seen one but they were supporting Taiwan's efforts, international efforts, because they knew they were important.”

Letters of Support for Black-faced Spoonbill Conservation in Taiwan (Source: TWBF Archives)

This advocacy did not sit well will some locals who viewed the bird as a threat to development. They figured that if they could get them to abandon the habitat, they could develop the land. Tragedy stuck on November 29, 1992. That day, over 520 empty bullet shell casings were discovered scattered in the Black-faced Spoonbill habitat. Three birds had been killed and many others injured.

Cartridges and Killed Black-faced Spoonbill (Philip Kuo)

The next two years would bring mixed results for the conservation of the Black-faced Spoonbill. In Sicao, the Old Annan Salt Pan south of the Zengwen Estuary was split in two to accommodate both conservation and development. The northern section's 1,100 ha would become the Tainan Technology Industrial Park, while the southern section's 515 ha would be designated the Sicao Wildlife Refuge. This was welcome news. However, in Chiku, a battle was brewing over the proposed industrial park.

In 1993 there was discussion of building a steel mill and petrochemical factory with the support of major corporations like Tuntex and Yieh Loong. This case, known as the Binnan development, garnered national attention as it would affect local people's livelihoods, environmental quality, and habitat for the Black-faced Spoonbill.

According to Dr. Severinghaus, "It was the Binnan development project that raised a lot of concerns. The bird people were involved first. But then you had other people who were concerned about different aspects of the environment such as fish biologists. They all banded together and it was a tremendous, united effort to block all of this. There were protest marches going to the Legislative Yuan, going to the COA, especially the COA. The Black-faced Spoonbill became a sort of mascot for this movement.”

Mr. Kuo added that for locals, "Because the industrial park would have needed a place for the sewage, it would’ve been impossible. There is so much aquaculture here, and there are a lot of juvenile fish here. Many different experts said it was an important place for biodiversity, but they used the Black-faced Spoonbill as the representative.”

Eventually, the project was put on hold for review. Thirteen years later, it was formally canceled.

The eyes of the world watching this play out in Taiwan. The country had a tarnished image due to past trade in tiger bone, rhino horn, and ivory, mainly for traditional Chinese medicine. It was hit with sanctions under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) and the U.S.'s Pelly Amendment in 1993. Dr. Severinghaus explained that the Taiwanese government was quite concerned about these developments and the central government, especially the COA, worked extremely hard to change attitudes at home and convince the international community they had changed as well (Taiwan would be removed from sanctions and taken off a wildlife product offender watchlist in 1996).

At this point, Taiwan had been doing weekly and monthly surveys of Spoonbills under Prof. Wang with the support of the COA since 1991. Local groups like WBS Tainan and TWBF were raising awareness and trying to change the conversation surrounding conservation at home. But, people like Dr. Severinghaus knew that as a migratory bird, protecting the Spoonbill population while it was in Taiwan would only ever be half the story.

So in 1993 when an international Black-faced Spoonbill census was discussed, Taiwanese conservationists were onboard. it would be organized by known range states and compiled by Mr. Tom Dahmer, an environmental consultant based in Hong Kong. He would continue to compile the survey results until passing the baton to the Hong Kong Birdwatching Society in 2002. The survey was originally planned to take place twice a year though it later was fixed as once a year, in mid-to-late January. The first full census report of 1994 reported less than 400 birds, with 90% of the population wintering in Taiwan. The other major wintering locations were Hong Kong’s Mai Po Wetland and the Red River Delta in Vietnam.

Also in 1994, discussions on how to better conserve the Black-faced Spoonbill along its range began in earnest as well. According to Dr. Severinghaus, "The wintering population is important, but we didn’t know anything about its breeding, or the factors related to its breeding success, or its migration route. If you only protect the wintering population, you could still see the population decrease.”

So, Dr. Severinghaus, then TWBF president, met with the head of BirdLife Asia on the sidelines of the 21st BirdLife World Conference held in Rosenheim, Germany in August of 1994. She explained: “At that time, the head of the BirdLife Asia Council, Dr. Noritaka Ishida, and Dr. Jong Ryol Chong of Korea University in Tokyo, the three of us discussed and decided right there that we would make the Black-faced Spoonbill a BirdLife Asia topic. I volunteered to raise money and write that action plan.”

Taiwan's Council of Agriculture would go on to sponsor the Action Plan draft meeting, which took place in January 1995, as well as the publication of the finalized first Action Plan for the Black-faced Spoonbill Platalea minor, which would come out in September. Coordinated and run by Dr. Severinghaus and the TWBF, the weeklong meeting brought together international experts on Spoonbills and representatives from all areas where the species had been recorded until that time. The goal was to develop a plan to stabilize the population of one of the world’s most endangered birds in one of the most geopolitically and culturally complex regions in the world.

At that point, most wintering birds were known to be at The Red River Delta in Vietnam, Mai Po wetland in Hong Kong and the Zengwen estuary in Taiwan. Though they were said to breed in the Demilitarized Zone between North and South Korea, there was still very little information on this and nearly no information about migration patterns. The action plan worked to address all these issues, detailing how to study and conserve the species locally and the kind of international collaboration needed. As the situation was unstable, it was agreed that a Task Force would be set up and a meeting would take place in the region each year to discuss progress. This happened until 2000. In 1996, the Task Force met in Beijing and in 1997 Tokyo.

From 1996 until 2000, Taiwan and the other areas along the range followed the Action Plan. However, Taiwan also had the capacity to share with others based on over five years of data by researchers and the experiences working with local communities by NGOs such as the WBS Tainan. The COA and other government agencies also encouraged such efforts for Taiwan to share knowledge internationally.

Dr. Severinghaus explains, “We did our best to help. We prepared all kinds of things. We prepared pamphlets in six different languages: Chinese, Russian, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and English. We printed huge stacks and mailed them to representatives all over so they could distribute them. These pamphlets laid out what a Black-faced Spoonbill was, how to differentiate it from ibis and egrets and how to do basic surveys. It also explained what to do if you found one.”

Photo by Philip Kuo

Taiwan also lent its support for conducting surveys. For instance, from 1998 to 2002, Dr. Woei-Horng Fang led teams from Taiwan to assist those doing Black-faced Spoonbill surveys in Vietnam's Red River Delta. As he puts it, "They needed help at that time and so we just filled in the gap. Then it was done by the BirdLife Vietnam Programme.”

As this concerted effort continued, Taiwan joined with others to learn more about the species behavior and migration. The year 1998 saw the first attempts at tracking the migration routes of Black-faced Spoonbills. In both Hong Kong and Taiwan three birds were fitted with radio trackers. Prof. Wang, who led the Taiwan team, explained that as this was new, they first tried to put the tracker on a Eurasian Spoonbill in the aviary of the Taipei Zoo to see if its behavior would be affected. Having shown no issues with flight or behavior, three birds in Tainan were fitted with trackers. Of the birds tagged in Hong Kong and Taiwan, only one from Tainan, a subadult bird, was successfully tracked. It flew from southern Taiwan to coastal China to rest. More tracking studies would follow but these initial efforts paved the way.

Back in Tainan, many groups were forming to help raise awareness or conserve the Black-faced Spoonbill and its habitat. One of those groups, the Taiwan Black-faced Spoonbill Conservation Association (BFSA), was established in 1998 to conserve parts of Chiku from being developed. According to the executive director of the organization, Dr. Tzu-yao Tai, the organization aimed to help with issues facing Black-faced Spoonbills and their habitat in Tainan County as opposed to Tainan City, which is where Sicao and the WBS Tainan were located.

Tai said, "Our goal was to protect the land and the environment and use the Black-faced Spoonbill as a flagship species. But we weren't only concerned with them. We were concerned with environmental and ecosystem protection. We'd hold events for local people as well and help to do the surveys… Local groups like ours let the fisheries people know that the Black-faced Spoonbills wouldn't impact their daily lives. In fact, when our organization just started, we spent a lot of time talking with people and letting them know that the birds wouldn't affect their harvests and played an important role in the local ecosystem.”

These efforts were paying off. The year the Kennerly report had been published, only 288 birds recorded. During the 1999-2000 survey, 660 were recorded with 380 wintering in Taiwan. Things seemed to be looking up. But there was much more work to be done.

Part Two: Coming Out April 29th