Let's Get Hei-Pi: A Review of Black-faced Spoonbill Conservation Efforts in Taiwan - Part 2

by Scott Pursner

Part Two of a Two Part Series

Photo by Philip Kuo

The Black-faced Spoonbill (Platalea minor), whose global population has risen from a known 288 in 1990 to over 5,000 this year, is one of Asia's great conservation successes. This endangered migratory waterbird endemic to East Asia has not just become iconic in countries along the East Asian-Australasian Flyway, but has won over the hearts of enthusiasts and the public around the world. Its conservation success relied on the power of partnership and cooperation at both the local and international level. Taiwan, which sees over half the global wintering population and where it is affectionately known as “Hei-Pi” (since the "hei" and "pi" of its Chinese name sound like "happy"), made outsized contributions to that success. Here we look at that story.

Part 2: 2000-Present, Conservation Challenges, Successes, and New Threats

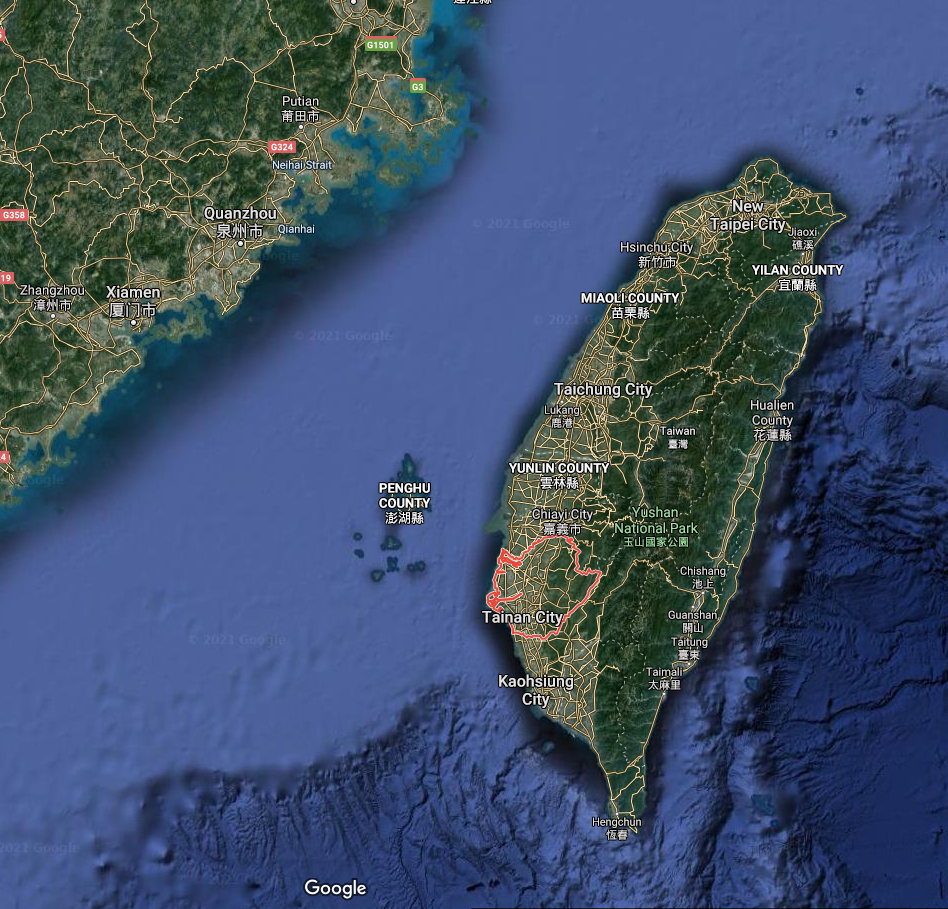

By 2000, efforts to conserve the Black-faced Spoonbill were well underway throughout the species’ range. The situation in Taiwan and internationally was vastly different than in 1990, when Peter Kennerly had sounded the alarm that there were just 288 of these unique waterbirds left in the world. One thing hadn't changed though, namely that Taiwan was still home to over 50% of the global wintering population. Though that population was slowly growing, at this point most of it was still located in southwestern Tainan, at the Zengwen Estuary.

Taiwan with Tainan City highlighted (Google)

Tainan and major areas for Black-faced Spoonbills (Google)

Local groups were busy. The Wild Bird Society of Tainan was doing surveys twice a month from October to May to record numbers. Also, alongside the Taiwan Black-faced Spoonbill Conservation Association and other groups, it would take part in the International Black-faced Spoonbill Census organized domestically by the Taiwan Wild Bird Federation. These organizations also did outreach and education work with locals. The goal as in the past was to try and protect habitat and win over hearts.

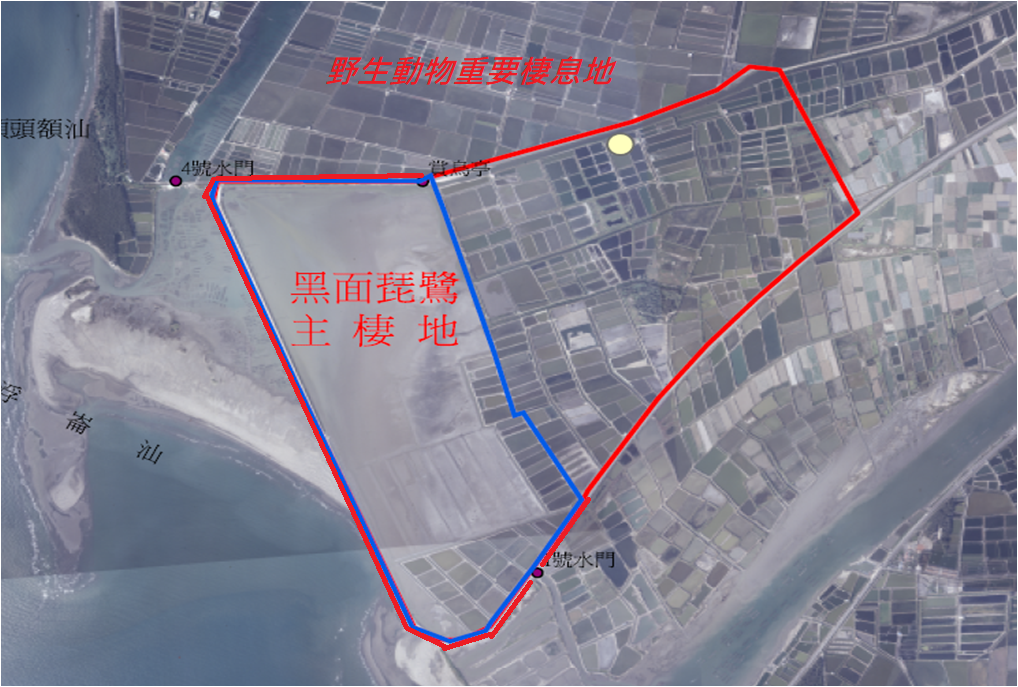

Also, as opposed to the fledgling international efforts of the early 1990s, Black-faced Spoonbill conservation had now become a major regional issue and an Action Plan for helping to conserve the species was developed in 1995. After that, regular meetings were taking place at the international level. In the fall of 2002, the bird was included in Appendix I of the Convention on Migratory Species under the United Nations. That same year, Taiwan's Forestry Bureau in conjunction with the Tainan County government created a second protected area for Black-faced Spoonbills in Tainan. The important wildlife habitat was located on 634 ha of land north of the Zengwen Estuary. Some 300 ha were designated as the Black-faced Spoonbill Reserve and another 334 ha of fish ponds were labelled a major wildlife habitat.

Close-up of the Black-faced Spoonbill Reserve and Major Wildlife Habitat, Philip Kuo

Disaster struck, however, in the Fall/Winter of 2002 with a botulism outbreak that killed 73 birds. At first, locals were concerned it was avian flu, but it was later discovered that there were fish and shrimp in the stomachs of the birds and so the deaths were attributed to botulism. It was such big news that international experts came to learn what had happened, including Dr. Sooil Kim of South Korea, the country's key Black-faced Spoonbill researcher at the time.

Photo A

Photo B

(Photos A-B, Botulism Outbreak of 2002, Philip Kuo)

This outbreak highlighted the need for more population dispersal amongst the wintering Taiwan population so that such a mass die-off would not happen again. Another effect of the outbreak was the creation of a standard operating procedure for handling wildlife crises of this nature in Taiwan. Funded by the government, drills to ensure preparedness and rapid response as part of this SOP were, and continue to be, coordinated by local groups such as the WBS Tainan and local and central government agencies. Individuals such as Taiwanese wildlife researcher and professor Prof. Ying Wang and former WBS Tainan and TWBF president Mr. Philip Kuo serve as committee members and participate in the proceedings. Topics addressed include rescue, treatment, and cleaning of outbreak areas. Mr. Kuo said of the SOP, "We hold the drills every September or October. Different areas take turns. So, it can be at Sicao [south of the Zengwen Estuary], or Chiku [north of the Zengwen Estuary], or Dingshan [north of Chiku]. We even helped the WBS Chiayi do the drills since now there are many Spoonbills in Chiayi County's Budai Wetland.”

Photo C

Photo D

Photo E

(Photos C-E, Wildlife Rescue SOP Drill, Philip Kuo)

Indeed, as a result of international efforts, the population was continuing to grow. In January 2003, the year that the reins of the International Black-faced Spoonbill Census were passed from environmental consultant Tom Dahmer to the Hong Kong Bird Watching Society, there were 580 Black-faced Spoonbills recorded in Taiwan. The survey, which counts the global population in all areas along the range had begun in 1994, when only around 400 in total were counted. But larger populations meant more habitat was needed. So Taiwan's wintering birds began spread out.

According to Prof. Wang, "From the early times there were 200 birds [in Chiku], occasionally 10-15 went to Sicao and the families got larger and larger. Then a few families got so large, after years you see Sicao establish a second population. From there they would go north to Dingshan and then Aogu [in Chiayi].

Now, Prof. Wang says,“Maybe there are 10 wintering habitats [for spoonbills] in Taiwan and so no one area is so important. Before we said Chiku, for their first 10 years, that was the wintering place. But then they went further north and south and diluted the power of one particular area.”

Black-faced Spoonbills can now be found wintering throughout Taiwan and its outlying islands with most in the area stretching from central Taiwan's Yunlin County to Kaohsiung City.

Taiwan was already at this point contributing to international efforts to band Black-faced Spoonbills as well. This was not easy though since there is a specific process for applying to band the birds and so most banded birds are rescues. Dr. Wang recalled that it was extremely hard to apply to the government to do banding. He did the first banding in 1997-1998. At that time Taiwan was given a specific international identification of a 'T' followed by two numbers on a blue band. It was only in 2021 that Taiwan used all the allotted band numbers available. Now, due to letter availability, Taiwan uses the letter "N". Already this year, N09 has been released.

Banded Black-faced Spoonbill, Philip Kuo

Another major local milestone was the founding of Taijiang National Park in 2009. The 4095 ha park encompasses areas in both Chiku and Sicao that are important to numerous migratory species, including the Black-faced Spoonbill. Once it was created, the park began to work on managing the artificial wetlands, fish ponds, salt pans, and farms which were under its purview. One major aspect of this was constant coordination and discussion with local fishers, farmers, and birders to promote sustainable use of the land. The park also hired groups like the WBS Tainan and the BFSA to aid them with surveys and public outreach and education.

Meanwhile, to help with recording sightings, in 2010 the BFSA created a website for sharing information. As Dr. Tzu-yao Tai, executive director of the BFSA puts it,“We wanted a place where people could see the records and put their own records, like eBird or iNaturalist (Two currently popular platforms for recording observations of birds and biodiversity, respectively). In 2010 it was a new idea.”Also, anyone could list their observation. Dr. Tai continued,“The website was so important because local people could take part in it. This data can help to contribute to the other major citizen science projects such as the Taiwan New Year Bird Count [Taiwan's version of the Christmas Bird Count].”

That year also marked 15 years since the first Action Plan for the Black-faced Spoonbill had taken place. In a meeting funded by the Convention on Migratory Species and organized by BirdLife International, a second action plan was created building off the success of the first. Representing Taiwan at that time would be Dr. Woei-Horng Fang, TWBF's current president since 2018. For Taiwan, the main responsibility would be to continue ensuring the safety of the Spoonbill’s largest wintering area and working closer with other groups to share its experience and conduct studies to better understand the birds and their needs.

In 2012 Taijiang National Park commissioned Prof. Wang for its Taijiang National Park Black-faced Spoonbill Population Distribution and Habitat Investigation Program. During the program, which was a collaboration between Wang, the national park and Dr. Kisup Li of South Korea, Black-faced Spoonbills were tagged with satellite transmitters and traditional radio transmitters to better understand their usage of wetlands in their range and global migration paths. There were seven Black-faced Spoonbills in the program, three tagged satellite transmitters, and four with radio transmitters. Meanwhile, one was tagged with a satellite transmitter and released on one of South Korea’s offshore islands. Bands were also placed on numerous birds as well. This information was later shared so that countries along its range, such as Korea, Japan, China, and Vietnam, could better understand the migration routes. Taijiang would also ask Dr. Wang to help develop management suggestions for the future.

Black-faced Spoonbill numbers have slowly increased annually and now the situation is viewed with cautious optimism. This has allowed for an expansion of conservation efforts. For instance, Taijiang National Park in 2016 began working with local fishermen do Spoonbill-related ecotourism and food labeling.

In 2016, the "Happy Milkfish" brand was developed to highlight fish grown using traditional methods which are good for spoonbills. According to Kuo,“The government has supporting measures. If the aquaculturist is willing to participate, they can help them to get a logo saying their food comes from a friendly habitat. This could bring in both money and the chance for ecotourism. People come to see the birds and then buy fish and other products. This has promise.”

In the fall of 2020, the TWBF helped to organize two different events with WBS Tainan highlighting Spoonbill-friendly agriculture and products. The events were a success and more are planned.

Photo from sustainable aquaculture event held in October 2020

Threats to the population remain throughout the range, including hunting, land exploitation, and the effects of climate change. For Taiwan, and particularly its southwest, one of the major challenges is the nation's shift to green energy. A focus on developing solar and wind power has been a hallmark of the current government's move to transition to a 20 percent renewable energy mix by 2025.

As flat land is a rarity, many photovoltaic projects have been proposed for or are already being built on wetlands. The Ramsar Convention, which is the United Nations major doctrine on protecting and effectively managing wetlands, states that wetlands supporting vulnerable, endangered or critically endangered species, or threatened ecological communities, should meet the criteria for Ramsar certification. This would allow them to be recognized as wetlands of international importance and possibly afford them better protections. But this is not possible for Taiwan.

As ornithologist and former president of the International Ornithological Union Dr. Lucia Liu Severinghaus puts it,“Taiwan is not part of Ramsar. We have 12 major wetlands here. Though they are not 12 of the largest or even 12 medium-sized wetlands by Asian standards, we need to protect them regardless of how big they are or how they rank internationally since we should do what is right for Taiwan. It doesn't matter if we are a part of it [Ramsar] or not.” So local conservation groups are working hard to ensure the voices of nature are heard.

Solar panels have already been developed in Sections 8 and 9 in Taiwan's largest wintering ground for migratory waterbirds, the Budai Wetlands in Chiayi. There were also plans for developing a photovoltaic project at the Jiangjun Wetlands just north of Chiku. Yet these 200 acres of former saltpans see over eight globally threated species winter or stopover there annually, including the Black-faced Spoonbill and critically endangered Spoonbilled Sandpiper. Protests from organizations such as the Taiwan Wild Bird Federation, the WBS Tainan, the BFSA, and scholars, put a halt to these plans.

Conservation groups are all watching these developments closely. According to Dr. Fang, "Currently there are not many threats to the Black-faced Spoonbill in Taiwan. We would like to see them expand their habitat area, but the national strategy for the solar panels doesn't leave a lot of space. Once wetlands become dry lands, Spoonbills will not use the areas. The land usage is the main point.”

He is echoed by Mr. Kuo, who said, "The habitat has become more complicated because of the solar panels. The number of photovoltaic panels will become more and more, just like at Budai now. We started to do surveys in October, there were more than 700 [Spoonbills] in November at Budai. From November to December it became 500. Then in January it was 300. Then by then end of the month 200. They obviously just headed south.”

So all eyes are turning to the Environmental Impact Assessment process, which gauges the ecological feasibility of development projects. Groups such as WBS Tainan and the BFSA are hoping to take part in more of the conversations surrounding the development of green energy in Taiwan.

According to Dr. Tai of the BFSA, "there are science evaluation committees which can determine if you can or can’t build in certain places because there are spoonbills there. And we can try to convince committee members with the science.” He continued, “Is this specifically about the Black-faced Spoonbill? Not exactly. It is more about the development of green energy. Done in the wrong area, it's a problem and one we are seeing more and more of over the last few years. You see in different parts of Taiwan. For instance, in Taoyuan it was putting solar panels in areas where there were traditionally small ponds. Here it's fish ponds, salt pans, farms and reservoirs. All have overlap with bird habitat.” There are many local environmental consultant groups and international investment companies who are interested in this information.

Another issue is management of the fish ponds. As most of these wetlands are not natural, according to Prof. Wang, you need to control the water levels and seasonal changes. If the government could launch a project for managing fish ponds, including private ones, an efficient management regime could be set up. As he puts it, "This would be a benefit for Spoonbill foraging and could predict where they would go. If we can manage the depth and harvest time [of fish] then they can be made to go where we want them to. We could start from the north if we know some fish ponds will start their harvesting. If they bring the water level down then the birds will come. They are relatively predictable. But more study is needed.”

Foraging Black-faced Spoonbills, Philip Kuo

Kuo agrees with the need for more effective management. He felt that as the population has grown, fewer use the area which once saw nearly the whole population. A better method is now needed. "There used to just be a few hundred, now it is already over 3,000. These birds need to eat, otherwise they could starve. You can't just give them a place to sleep, they need a dining room too,”he said.

Taiwanese conservationists and local groups continue the work to save Black-faced Spoonbills and their habitats which they started so long ago. For the BFSA, besides doing knowledge-sharing with international friends as well as surveys, they are focusing on the next generation. The organization has converted an old elementary school into an office and continues to promote popular science. They also have adopted 500 ha of saltpans next to the school to do some habitat management. According to Dr. Tai, this is the method they wish to develop going forward. As he puts it, "This allows local people to come and look and experience the wetland.”

Another important activity is interacting with the next generation online and offline. Facebook has become one of the main venues for interacting with younger people. Meanwhile, the BFSA will have events for all kinds of groups but especially local elementary school children so that they can learn to appreciate nature and science. To do this, it will hold camps and do school visits as well. As Dr. Tai says, "We need to do this in order to have a future.”

Kuo and the WBS Tainan have participated in numerous international conferences. In 2019 he participated in an MOU signing with groups from Japan, South Korea, and Hong Kong towards better knowledge-sharing on the migrating Black-faced Spoonbills. He also has worked to help Chinese scientists across the strait. He mentioned that in the past he helped make a film on Taiwan’s botulism SOP for Chinese conservationists and was also going to help another group from Dalian with making another film, but it was not possible due to COVID-related issues.

As he put it, “I'm very willing because it's experience-sharing. That's how it works. We'll help you understand the way our SOP works. This is important since we all need to help each other. He added that areas such as the Chongming Dongtan at the mouth of the Yangtze and Xingrentouzi and Yuanbaotouzi islands of the Shicheng Island group in Liaoning in China, as well as the artificial islands of Incheon Songdo International City in South Korea, share many similarities to Taijiang National Park in Taiwan.

As it stands, this year has been the biggest year for Black-faced Spoonbills, with the global population crossing the 5,000 threshold for the first time ever. It is also a record for Taiwan, with over 3,000 birds counted.

So, what has Taiwan done? In the words of Dr. Severinghaus who served as TWBF president during the major Black-faced Spoonbill campaign in the 1990s, "Taiwan's sharing and support of others were really important. Taiwan and TWBF, supported by government and other groups, helped to organize through BirdLife a fantastic international collaboration effort. You know there were so many international ecological collaborations represented at the 2000 BirdLife International meeting. I was asked to present what was happening for Black-faced Spoonbill conservation. I was told that [this effort] was the standard for successful cooperation and successful conservation efforts. Even now the count helps to monitor things. I am sure that even if now there is a crisis, people will come together.”

Kuo said, "Generally due to traditional aquaculture practices, the southwest coast was a good option for the birds and so they made the choice to winter here and liked it. Taiwanese gradually learned to appreciate them. Now we face this photovoltaics issues which endangers its habitat. We made some smart moves early, and we hope that the reserves can help them to improve their numbers. Who knows, hopefully one day there can be 5,000 or even 10,000 here in Taiwan!”

And Dr. Fang was a bit more candid.“We really didn't do anything besides try our best to keep their habitat safe. Taiwanese will continue to do that. But it really depends not just on the wintering grounds, but the breeding grounds especially along the western coast of the Korean peninsula. That's why conservation is such an international issue, everyone must work together for it to be a success.”