Return of the Mythical Bird: Conservation Efforts to save the Chinese Crested Tern in Taiwan

By: Scott Pursner

A Chinese crested tern sits among agroup of Greater crested terns (Photo: Wild Bird Society of Taipei)

The last time the Chinese Crested Tern (Thalasseus bernsteini ) had a confirmed record was off the coast of China's Shandong province in 1937. Since then, scientists and researchers alike had thought it had gone extinct, leading to its nickname, 'the mythical bird'. Yet in 2000, Taiwan's Matsu archipelago played host to an ornithological miracle—the rediscovery of the CCT after almost 70 years. Since then, Taiwanese conservationists and researchers have been fighting save the world's most critically endangered seabird from vanishing for good.

Re-Tern of the CCT

"The story of the CCT's return to the world stage is actually pretty interesting. All this time, it was hiding in plain sight in the Taiwan Strait, one of the most populated areas in the world," said Allen Lyu, vice secretary-general for the Taiwan Wild Bird Federation. "It was only rediscovered by accident while making a documentary.”

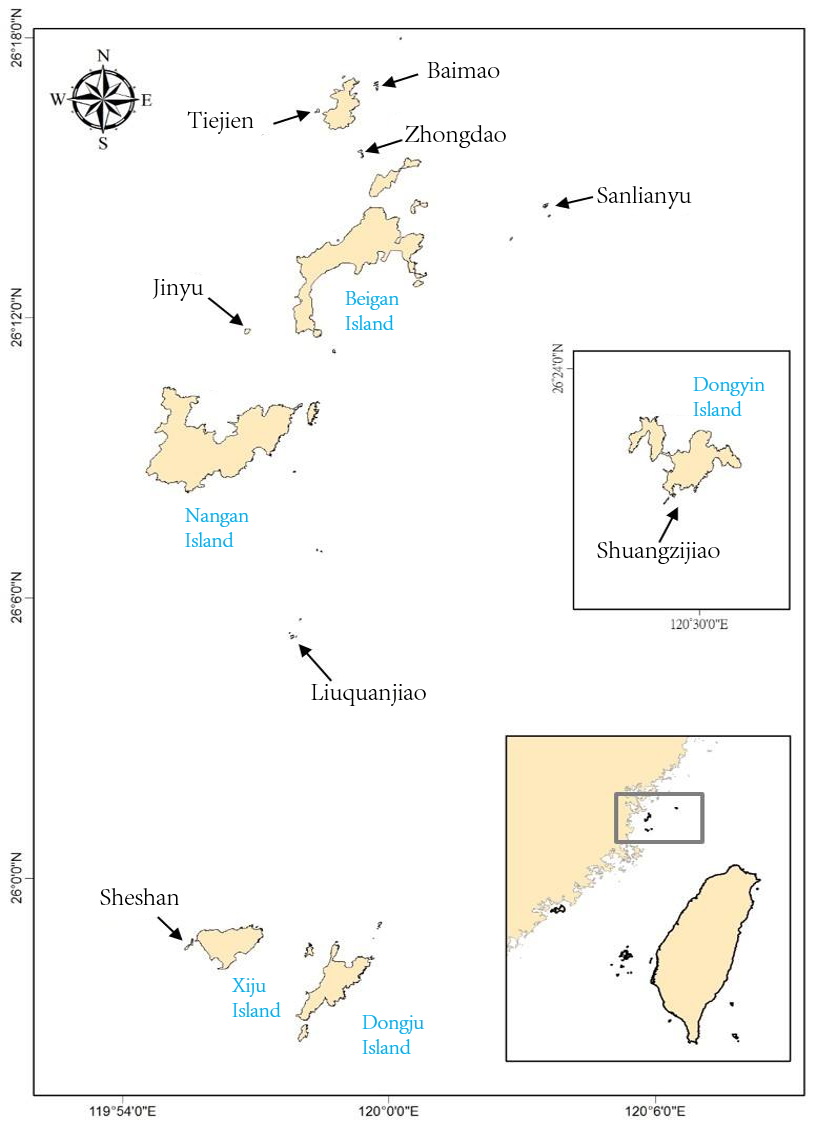

By 'accident' Lyu was referring to how it was a perfect storm of events that led to the discovery. The Matsu Islands, where the find was made, lie just off the coast of Fujian province in China. For almost 50 years, the small archipelago served as a Taiwanese military outpost with restricted access to all but military personnel and local residents. It wasn't until the mid-1990s with tensions cooling across the Taiwan Strait that the islands were opened to the public. Birdwatchers jumped at this chance as Matsu hosts a number of seabirds, particularly birds from mainland Asia that can't be seen in Taiwan. It was at that time that the TWBF, then known as Wild Bird Federation Taiwan (WBFT), applied to conduct surveys of Matsu's 36 islands to learn more about the wildlife situation there. It was known that large numbers of seabirds were using some of the uninhabited rocky islands for breeding. Thanks to the surveys, eight islands were later declared as the Matsu Island Tern Refuge in 2000. Lyu added that at that time, many local people were still fishing and harvesting seafood in the area. The TWBF then hired director CT Liang to create a documentary to raise awareness about islet ecosystems and their importance. In the end, it was Liang who first noticed that some of the Greater Crested Terns (GCT) he was filming seemed a bit off.

Taiwan, it's major outlying islands and the Matsu archipelago (major island names in blue, Matsu Islands Tern Refuge Islands have arrows)

Tiejien Island, Matsu Archipelago, Taiwan (Photo: Wild Bird Society of Taipei)

Lyu explained, "For tern species, like gulls, slight differences in certain features are what it's all about. The biggest difference between CCTs and GCTs is that the GCT has darker grey wings and a fully orange bill, while the CCT has much lighter-colored wings and a blackish bill tip.”

A Chinese crested tern stand nest to a Greater crested Tern (Photo: Dr. Chung-hang Hung)

Liang sent his footage to WBFT, which confirmed that the birds captured on video were in fact different. With a total of eight adults and two chicks recorded, the CCT was brought back from being presumed extinct to being critically endangered. At that point, nobody knew how many there were, but scientists and conservationists wanted to find out.

Taiwan's foremost CCT researcher is Dr. Chung-hang Hung, a Ph.D. post-doc at National Taiwan University (NTU) in Taipei. Hung began researching the CCT in 2010 under the one professor doing CCT work at the time, Dr. Hsiao-wei Yuan. He said that soon after the discovery in Taiwan, another breeding group was spotted in China's Zhoushan Islands off the coast of Zhejiang province. The second find electrified the international community. In 2002, it was listed as an Appendix 1 species in the United Nations Environmental Programme Convention on Migratory Species. The inclusion marked a big step forward in CCT conservation work as it highlighted the risk of extinction in some or all of its range and advised that it should therefore be protected by all range countries in which it appeared.

In 2006, a major meeting took place with Dr. Yuan of Taiwan, Dr. Shui-hua Chen of China and Simba Chan of BirdLife International Asia Division. This meeting would subsequently lead to the inception of the International Single Species Action Plan for the Conservation of the Chinese Crested Tern. The plan set out guidelines and goals for protecting the fragile population. At the time, it was thought that the global population stood at no more than 50 individuals.

Conservation through Research

In Taiwan, local conservation groups and researchers, with financial support from local government and government agencies such as the Forestry Bureau, have led the way in CCT conservation. In 2008, the Wild Bird Society of Taipei (WBST) began helping the Wild Bird Society of Matsu (WBSM) with its CCT work. Being partners of the TWBF, both organizations could consult with each other and lend support if needed.

Arthur Chiang, head researcher at the WBST and Ph.D student under Dr. Yuan, has been working on CCTs since 2011. WBST has been one of the local groups most actively working to learn more about the seabird's population and migration dynamics. He explained that in the beginning, local researchers knew that CCT breed in groups of GCT. Therefore, plans were developed to learn more about where the GCTs wintered.

"CCTs and GCTs only stay in Taiwan between April and September. By early September, they will all be gone,” he said, adding that "with this in mind, in both 2008 and 2015, WBST, via a National Taiwan University project, carried out satellite tracking on GCTs to better understand their range. Already from our work, we know that there are two major population groups which come here for breeding. One generally winters in Thailand and Cambodia in Southeast Asia and the other goes somewhere in the Philippine Sea," he said. Some currently confirmed wintering sites include Davao City in the Philippines, Sarawak in Malaysia, and certain islands in Indonesia. As for staging sites in Taiwan, CCT are now known to use the Jishui and Gaoping Rivers in southern Taiwan as well as Yilan's Lanyang Rivermouth in the north.

Researchers return to breeding site at Tiejian Island after breeding season to collect and clean decoy birds (Photo: Chung-hang Hung, October 2017)

In the past, WBST also did GCT bird banding. Now, this work is mostly handled by Dr. Yuan's students at NTU's School of Forestry and Resources Conservation in coordination with WBST and with support from TWBF. According to Hung, from 2008-2019, 227 adults and 562 chicks were banded. Tracking the banded birds has revealed that the Matsu visitors will also sometimes fly to Taiwan's Penghu archipelago or other islands off the coast of Zhejiang province, China. These results informed researchers that they are dealing with a metapopulation, which is positive for population stability.

Current known breeding sites for the Chinese Crested Tern include: a) Matsu Islands, Taiwan b) Wushisan Islands, Zhoushan City, Zhejiang Province, China b) Jiushan Islands, Xiangshan, Ningbo City, China d) Penghu Archipelago, Taiwan e) Jeollanam-do, South Korea

For all the banding of GCTs which has taken place though, the same cannot be said of CCTs. In 2015, Dr. Yuan's lab was the first in the world to successfully band the rare seabird. The juvenile female was given the number A74. Locally known by researchers as Matsu girl, she's come back every year since. The banded bird provided conservationists a rare opportunity to learn about CCT breeding behavior and life history. In 2018, she even returned with a partner and displayed breeding behaviors. However, the breeding site was destroyed by a typhoon. Only one other CCT has been banded in Taiwan, bringing the total to just two.

Matsu Girl, A74 (Photo: Wild Bird Society of Taipei)

Situation on the Ground

Within Taiwan, the fight to save the CCT has been filled with challenges. Chiang said that the WBST has worked hard to promote conservation via education and outreach. To this end, they've held events such as specimen presentations and educational events including games and interactive activities. The group has also tried to hold talks with local government about better conservation planning. "When the local [Matsu] government thinks of CCT conservation, they often think of it in terms of ecotourism and how it might bring economic opportunities to locals. This doesn't always run in sync with conservation goals. Changing that perspective is something we've been working on,”he said.

For Hung, more work on the local level is needed to help protect CCT breeding sites. "We don't have the problem of egg collection by locals threatening the birds like they do in China. The problem we have faced and still face is that fishermen will use areas near the islands for fishing or harvesting seafood. They'll also go to the islands at low tide to collect seaweed. This is illegal but there isn't very good enforcement of refuge rules.”Hung here is referring to the protected lands law which states that islands in the refuge and their surrounding waters are supposed to be off limits to fishermen.

Researchers with Wild Bird Society of Taipei use drone to look for CCT nests (Photo: Wild Bird Society of Taipei)

Also, though a government-run program to monitor the areas around the refuge exists, a comprehensive system for scheduled patrols by observers has not been developed. Hung continued, "If there was the opportunity, I would like to see young people with passion become Matsu Island Tern Refuge Wardens. They could have a boat and patrols could be carried out 24/7. They could also issue fines that have teeth. Right now, this doesn't really exist even though such things are on the books. It's the best way to protect critical CCT habitat.”

Bright Future for the Mythical Bird

Twenty years since its re-discovery, the current situation is still a fight against time. It is estimated that there are currently only 100 CCT on earth.

"The global population is extremely small, which makes it unstable. Thankfully in Taiwan the number of birds which return each year remains pretty steady," said Chiang. Generally speaking, about 10-20 CCT will come to Matsu for breeding, up to one fifth of the global population, he added. Others will breed in certain select locations along the coast of China. It was also recently discovered that a few other CCT were found to be nesting on an island off the coast of South Korea.

A CCT nesting in Matsu, Taiwan (Photo: Chung-hang Hung)

Although a Species Action Plan exists, a coordinated plan of action incorporating all countries and territories along its migration route has yet to be successfully developed. Cooperation does come in the form of meetings and talks with other groups working on CCT conservation. According to Hung, every year Taiwanese researchers and their Chinese counterparts will hold talks to discuss the progress made in CCT research and conservation. The location for the event alternates each year. This year, it will be held in Matsu. He added that after the discovery of the CCT in South Korea, NTU contacted the seabird researchers at the National institute of Ecology in Seocheon County, South Korea to ask them to participate in the gatherings as well.

Hung added that nobody can be certain about the fate of the CCT, but that those fighting to help protect this mythical bird would continue their fight. "From here in Taiwan, we are doing our best. It would be great if we could work more with other international groups along the CCT's migration route. It's the most endangered seabird, not just in Asia, but the world," he added.

Drone Footage of CCT and GCT breeding site at Tiejien island, Matsu Islands, Taiwan

- Footage courtesy of the Wild Bird Society of Taipei