Soaring on the Wings of Giants—35 Years of the Taiwan Wild Bird Federation (Part 2)

By Scott Pursner, TWBF Director of International Affairs

Part 2: The Founding of the TWBF and its Partners and Early Actions (Late 1980s-2000)

Being Established in a Time of Change (mid-1980s to 1989)

By the mid-1980s, Taiwan's rapidly growing middle class was paying greater attention to environmental as well as conservation issues and growing more and more interested in birds. It was at this time a new checklist for Taiwan's birds was proposed. Taiwan's three birdwatching groups met in 1985 for what could be described as Taiwan's first attempt to review its bird data collected by birders. There were two meetings held, with scholars and academics invited to attend. In total, 19 new species records were shared, but there was no final adoption of the results (5).

In 1986 discussions of how to represent Taiwan and its ornithological efforts abroad were taking shape. By this point, various academics and government-approved groups were in contact with the International Council on Bird Protection. The international group had even written to the Taiwanese government in 1985 asking about the conservation status of certain bird species like the Mikado Pheasant, Swinhoe's Pheasant, Elegant Scops Owl, and Chinese Egret (9). This led government agencies and government-approved NGOs to meet and discuss how to integrate Taiwan's conservation work with global efforts.

Elegant Scops-Owl (Source: TWBF)

The ICBP established closer links with Taiwan and supported its efforts in conservation. In turn, Taiwanese researchers and groups supported the ICBP's conservation programs. In 1986, Dr. Lucia Liu Severinghaus represented the Society for Wildlife and Nature of the ROC (SWAN) at the 1986 World Conference of ICBP in Canada (9). At the meeting, she stressed that politics has no place in conservation, as birds do not know borders. She added that Taiwanese conservation efforts needed international recognition and support, and that they should not be excluded from joining international organizations. Using this as a launching point, and after numerous meetings with the ICBP, the group later revised its regulations to accept members from outside the United Nations. Eight years after that meeting in Canada, the TWBF signed the paperwork to become an affiliate of the successor to the ICBP, BirdLife International (9).

Domestically, the heads of the three major bird groups in Taiwan met in 1986 to discuss the creation of a national-level bird conservation organization, with the thinking that such an organization would improve coordination, create a platform for sharing information, and provide a stronger voice for local groups in interactions with the government. In the words of one of the founders and a former president of the TWBF, Dr. Fang Woei-horng, "In the beginning, people all agreed that we needed a national-level type body because if we remained local societies, nobody would be strong enough to talk with the central government." The organization as planned would also serve as a more united voice in discussions with international NGOs outside of Taiwan (3). Noting that one of the main functions of the group was to help represent the three organizations, L. Severinghaus recalled that its founders hoped it would be able to create a "unified voice" to take advantage of international opportunities. To address the major concern that the organization would render existing groups obsolete, she added it was agreed that the new organization would serve as a secretariat, with local bird societies inducted as partner organizations.

It would be two more years, however, before the organization was officially formed. In 1987, martial law was lifted in Taiwan, with one of the effects being the removal of the requirement that civic organizations affiliate with a government-approved organization. Time was required to adjust to the new bureaucratic order. Though the Wild Bird Society of Taipei created its own group in 1984, the Wild Bird Association of Taiwan in Taichung did not change its status until 1991, and the Kaohsiung Wild Bird Society did not receive approval from the city government to be a bird society until 1993 (3). Yet on July 31, 1988, the thirty delegates required to establish a national-level organization met, discussed, and signed the paperwork to found the Wild Bird Society of the Republic of China, today known as the Taiwan Wild Bird Federation. This unified voice for local bird societies started with three members, or partner organizations, and was initially located in the same building as the Wild Bird Society of Taipei. The organization, founded by local birdwatchers and nature enthusiasts, adjusted its focus from pure birdwatching to include conservation components as well.

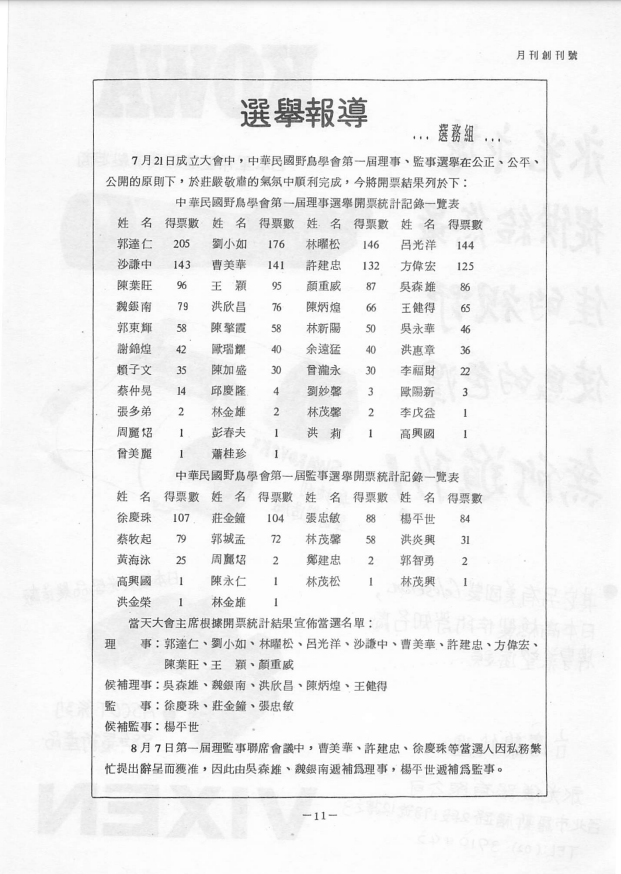

Results of the vote for TWBF's first Board of Directors and Supervisory Council (Source: Periodical of the WBSC Vol. 1 No. 1)

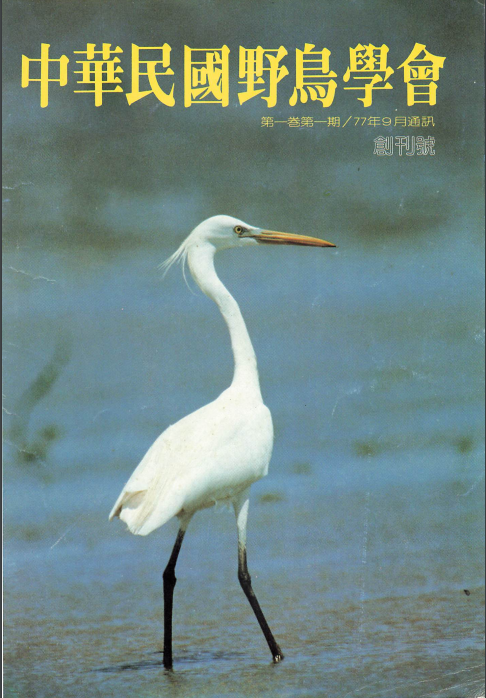

The organization started its own official periodical, The Periodical of the Wild Bird Society of the ROC. Launched in fall 1988, the magazine covered birdwatching trip reports, articles on local ecology, new checklist information, stories about conservation issues, and local reports by member societies. Feather Magazine served as an important resource on birdwatching and conservation before the advent of the internet. A year leater it would be renamed Feather Magazine by a vote from the TWBF's Board of Directors and Supervisory Council (Attachment 2).

Cover of the Inaugural edition of the Periodical of the Wild Bird Society of the ROC. It would be renamed Feather the next year (Source: TWBF Archives)

The new organization also undertook responsibility for a number of activities still in the planning or launch phases, including the collection of checklists and bird records. By 1984, the Wild Bird Society of Taipei had begun to collect checklists from members, yet many birders did not share their lists. In 1987, the Taiwan Bird Record Database was launched. According to Fang, it was managed by the TWBF and relied on DBase, an early data management system which allowed for records to be submitted on paper and entered into the system manually. Though many were reluctant at first, over time more and more people came to accept the idea. In 1998, the system shifted to Windows 98. Though an arduous process at first, the database later served as the foundation stone for a generation of bird conservation work and would be used for many conservation efforts in the future.

Another action in which the TWBF became involved was the Asian Waterbird Census. As Fang explained, in 1987 he was at the office of TWBF's first president Guo Da-ren. Guo, a dentist by trade, had received a letter from Wetlands International about participating in the newly initiated census which looked at wintering waterbird species throughout Asia. With Guo's approval, Fang coordinated Taiwan's participation in 1988, surveying 27 sites by means of connecting with the existing network of birders across Taiwan. Fang continued to compile Taiwan's AWC data for much of the next 20 years on behalf of the TWBF, and this data was later added to the Taiwan Bird Record Database.

Bird banding was another area in which the TWBF was active. Most banding activity stopped after the MAPS program of the 1960s and early 70s, except for efforts by a few individuals such as Dr. Peter Chen and Yan Chung-wei. By the late 1980s, Taiwanese researchers and NGOs were receiving queries about bird banding in Taiwan. Dr. L. Severinghaus recalled being contacted by Dr. Ishida Noritaka, her colleague at the Wild Bird Society of Japan, who had come to Taiwan in the late 1970s to discuss the problem of hunting Grey-faced Buzzards and who was very close with the Taiwanese researchers. Now he was interested in discussing Taiwan’s bird banding. Fang added that the WBSJ and the Australia Waders Group contacted the TWBF on this topic. According to him, these groups wanted Taiwan to begin banding since birds banded in Australia were recorded showing up in Japan, and they wanted Taiwan to help fill in gaps surrounding their migration paths. Bird banding in Taiwan had to be started from scratch in many respects. In the north, WBS Taipei volunteers went to northern Taipei's Guandu area to set up mist nets and do banding at night when it was easier to catch birds. Severinghaus explained that meetings to discuss banding were later held with the Council of Agriculture, which agreed that there should be one group charged with managing bands for Taiwan – the TWBF.

1989 witnessed a milestone for conservation in Taiwan. After five years of legal battles, Taiwan's Wildlife Conservation Act became law. This landmark legislation, based on the American Endangered Species Act, listed Taiwan's threatened species, with placement on the WCA list providing the possibility of legal protections. That year, another attempt was made at reviewing Taiwan's bird records (5). The TWBF called this second review meeting in January 1989. In total, 16 new records were approved. Yet with no formal written report, the only record of the report and semi-official record of the event was an article in the next day's Minsheng Daily (5).

Between 1989 and 1999, the federation expanded rapidly as bird societies were founded in more cities and counties. Groups which later became partner organizations that were founded during this period include Wild Bird Society of Nantou, Wild Bird Society of Hsinchu, Wild Bird Society of Hualien, Wild Bird Society of Keelung, wild Bird Society of Changhua, Wild Bird Society of Tainan, Wild Bird Society of Kinmen County, Wild Bird Society of Penghu, Meinung People's Association (Kaohsiung), Wild Bird Society of Taoyuan, Wild Bird Society of Pingtung, and Wild Bird Society of Taitung. It was also during this time that Taiwan came into the global spotlight, as Asian conservationists and NGOs were beginning the campaign to save the Black-faced Spoonbill.

Taiwan Conservation Arrives on the World Stage (1989-1999)

Little was known of the Black-faced Spoonbill, a waterbird endemic to East Asia, until Peter Kennerly of the ICBP in Hong Kong decided to investigate its numbers and distribution in the late 1980s. He initially wrote to Lin Chih-cheng, a fertilizer company owner in rural Miaoli County who he had met at an international meeting. Lin shared the correspondence with the WBS Taipei and soon a group was formed to survey the Zengwen Estuary in Tainan County where the bird was known to winter. Kennerly would later publish his findings in a 1990 report. It revealed that there were just 288 of the unique waterbirds between Taiwan, Vietnam, Hong Kong, China, South Korea, and Japan. Taiwan had 52% of the global wintering population of this critically endangered population. Locally, people were confronted with the significant presence of a species that hadn't been on the radar until then (7).

A Black-faced Spoonbill with Breeding Plumage (Source: TWBF)

Researchers who also served on the TWBF's Board of Directors such as Wang Ying were soon working on plans to help study the birds and better understand their distribution and ecology. Yet much of the protection work on the ground was done by the Wild Bird Society of Tainan (founded 1992), which worked diligently with the researchers to survey the birds at night to understand their numbers and behavior. Also in 1992, the Black-faced Spoonbill became the first migratory species to be added to the Wildlife Conservation Act list of protected species. Efforts were also aided by the founding of the Taiwan Endemic Species Research Institute (now known as the Taiwan Biodiversity Research Institute) that same year. This government institute was founded with the goal of conserving Taiwan's existing endemic species and genetic diversity as well as sustaining ecological balance in the long term (10). The group became an important partner for Taiwan's conservation NGOs.

Collaboration with international groups was critical to conservation success for the Black-faced Spoonbill. The TWBF asked friends at the Wild Bird Society of Japan (WBSJ) to provide them with materials on how to create wildlife conservation areas while also facilitating development. As part of a letter writing campaign, the TWBF called upon members of the global community to send messages to local and national officials asking them to save the Black-faced Spoonbill. Then in 1993, Taiwanese researchers joined in discussions regarding the holding of an annual international Black-faced Spoonbill census covering all areas it was found. The first full census report of 1994 reported less than 400 birds, with 90% of the population recorded wintering in Taiwan (7).

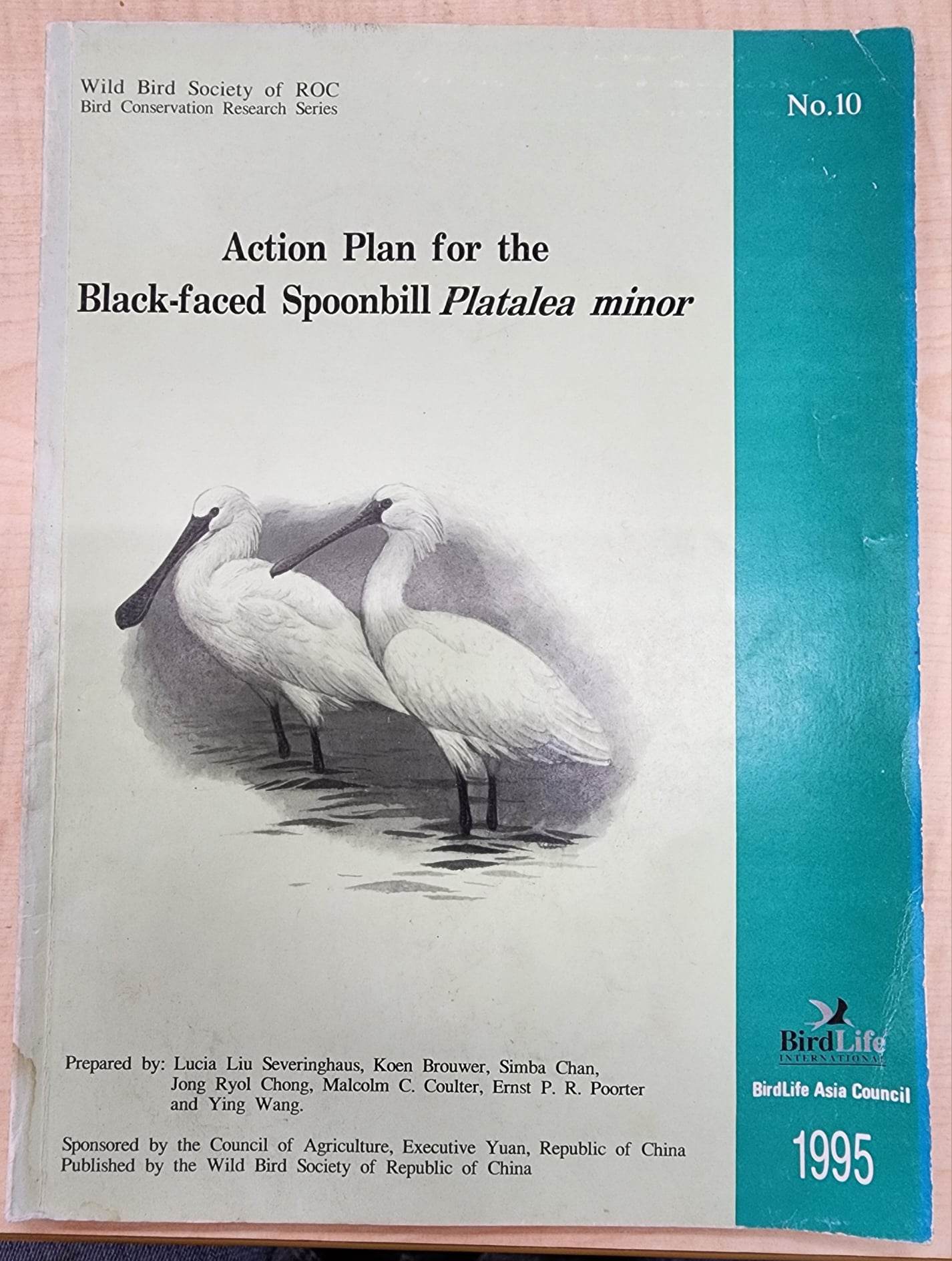

Yet even as late as 1994, Severinghaus explained that not much was really known about the the bird's breeding or migration. Then serving as TWBF president, she met with the head of the newly formed BirdLife Asia Division on the sidelines of the 21st BirdLife World Conference in Germany. Along with the head of the BirdLife Asia Council, Dr. Ishida Noritaka, and Dr. Jong Ryol Chong of Korea University in Tokyo, it was decided that the Black-faced Spoonbill would become a BirdLife Asia topic. Severinghaus volunteered to raise money and write the relevant action plan. Taiwan's Council of Agriculture (now Ministry of Agriculture) later sponsored the Action Plan draft meeting, which took place in January 1995. They also supported the publication of the first Action Plan for the Black-faced Spoonbill Platalea minor, which came out in September that year. The meeting was coordinated and run by Dr. L. Severinghaus and the TWBF (7).

The first Action Plan for the Black-faced Spoonbill (Platalea minor) (Source: TWBF Archives)

The action plan detailed how to study and conserve the species locally, as well as the kind of international collaboration needed. A task force was also set up to discuss progress, and met in Beijing in 1996 and Tokyo in 1997 before returning to Taipei in 1998 (7).

During the mid-1990s, Dr. L. Severinghaus served as president of the federation for one term although she was a board member for many years. As she explained it, while in office, she amended the constitution to ensure fair representation among the different partners. There was also an awareness that different regions of Taiwan might face different sociological or ecological concerns. As she put it, "While I was president, one thing that I did was make sure we represented everyone. I requested that the head of every society come to my monthly meetings. It could be the president or the director general but they would need to come up so we could discuss TWBF affairs. This would be necessary until we all felt it wasn't. Another was that we needed an official accountant to ensure our finances were secure. Finally, there was the matter of representation. How many representatives should each group get at the General Assembly? That was decided by me. For every 100 people who were members of the partner organization, they got one representative, and less than 100 got a minimum of one representative. This is the method still used today. This may have upset the bigger groups, but fair is fair, and giving groups regardless of size their voice could help the TWBF to become an appropriate representative to the outside.”

During her tenure, Severinghaus also sought to create an official checklist of the birds of Taiwan. According to her, prior to this, "There was a checklist done by the Wild Bird Society of Taipei and they had many good birdwatchers. So using this and coupling it with the information from the Taiwan Bird Records Database, we tried to rebuild the checklist." The TWBF would go on to be charged with the Checklist of the Birds of Taiwan (13).

Severinghaus was also instrumental in helping the TWBF join BirdLife International (formerly the International Council on Bird Protection) in the mid-90s. The strong relationship between the ICBP and Taiwan which began in the 1980s continued when the organization was relaunched in 1993 as BirdLife International. The TWBF officially became a Partner Designate in 1994 at the same meeting in Germany where it was decided the Black-faced Spoonbill would become a BirdLife Asia topic. Two more years passed before the organization became an official BirdLife International partner, which took place at the 13th BirdLife Asia Conference and 1st Pan-Asian Ornithological Congress held in Coimbatore, India in November 1996 (2). With this, the Taiwanese NGO officially joined the BirdLife family and took its place alongside its neighbors and friends in working towards conservation goals for birds.

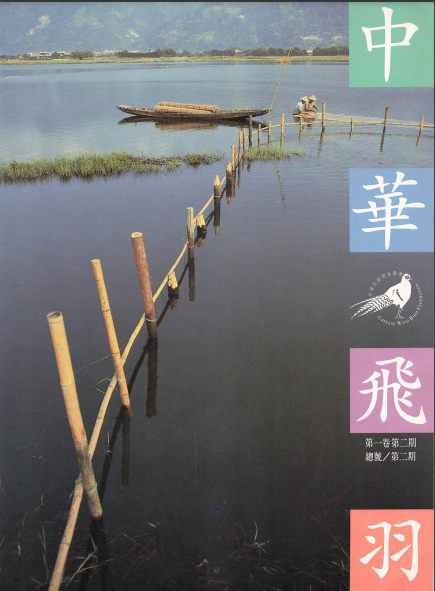

The organization was missing an official mascot, however, and according to Fang, a vote was held at a board meeting that year to decide which bird should represent the federation. The Mikado Pheasant won out in the end, and was selected for a few different reasons. First, although the official name for the species in Mandarin is 黑長尾雉(Hēi cháng wěi zhì) which roughly translates to Black Long-tailed Pheasant, it is more commonly known as帝雉 (Dì zhì) which means Emperor Pheasant and is more aligned with the English name which originates with the Japanese name for emperor, Mikado. This name sounded impressive to those taking part in the discussions. Second, the Mikado Pheasant is an endemic species, a representative of birds only found in Taiwan. Third, it is big enough to be seen easily without binoculars. Fourth, as opposed to certain other endemics such as the Swinhoe's Pheasant, it has a very distinctive look. Fifth, as a species found at high elevations, the newly founded organization could be considered in high regard and important in the conservation of birds. The first time the Mikado Pheasant made its debut as the official mascot was in the first color Feather Quarterly in 1996 (1). It was also the same year that the federation's English name switched from the Wild Bird Society of the Republic of China to the Chinese Wild Bird Federation.

The first time the Mikado Pheasant featured in a TWBF publication was 1996 (Source: TWBF Archives)

One of the defining projects taken on by the TWBF and its partners during the late 1990s was the establishment of Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas (IBA) in Taiwan. The purpose of IBAs was to promote the importance of habitat conservation by using birds as indicators of biodiversity. In the case of resident birds, this designation could lead to regional area protections; for migratory species, it could lead to better coordination beyond borders for the conservation of species. This would not only help establish comprehensive conservation networks necessary to maintain migratory routes, but would also foster international collaboration. Such certification offered to help protect important habitats, given that Taiwan is unable to receive RAMSAR or UNESCO designations since it is outside the UN system. As BirdLife International was charged with the certification process of IBAs, the TWBF as an official partner worked with its own partner organizations to draft a list of the sites important to Taiwan’s birds. Much of the data used in the discussions came from records in the Taiwan Bird Record Database, and checklists done during this project were also added to it as well.

In 1994 and 1996, the TWBF participated in preliminary meetings on IBAs, yet the project took off domestically only in 1998. Between 1998 and 1999 the TWBF held eight different meetings with its partners and international groups such as the Wild Bird Society of Japan to share information and prepare their case for IBAs in Taiwan (2). In 1999, the TWBF hosted the 1999 International Conference on Important Bird Areas as well as the 1999 BirdLife International Nature Reserve Management Seminar. At both events, representatives from all over the BirdLife Partnership attended to discuss the work of developing IBAs and how to use them for conservation. As Fang put it, "We had the IBA conference and a workshop at the Free Buzzard at Mt. Bagua [an event started by the TWBF partner, the Wild Bird Society of Changhua]. Then organization president Simon Liao mobilized all partner organization presidents to join these activities. There were international delegates like the BirdLife International Global Council chair as well as representatives from the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds in the UK and Wild Bird Society of Japan. Future BirdLife CEO Marco Lambertini was also there. The event was so big a meeting was even held with then-Taiwan President Lee Teng-hui.”

A photo from the meeting with President Lee in 1999 (Source: TWBF Archives)

The group discussed the importance of conservation and international cooperation with President Lee. Eventually, the TWBF submitted documentation for 52 IBAs in March of 2000, of which 51 were confirmed. More would be nominated over time, and areas designated as IBAs still remain important today (2).

Another BirdLife Initiative with Taiwan and the TWBF was the creation of BirdLife International's Threatened Birds of Asia—the BirdLife International Red Data Book. As Fang recalls, it was under the TWBF presidency of Guo Cheng-yu (1997-1999) that Taiwan and TWBF became involved. The purpose of the book was to highlight species under threat in Asia so that more work could be done to understand those at risk and do more to protect them. As with the IBA project, Taiwan's data relied again on the information of the Taiwan Bird Record database. The first edition was published in 2001.

Important Bird Areas in Taiwan First Edition (Source: TWBF Archives)

Yet another project to rely on the Taiwan Bird Record Database was an attempt at a Breeding Bird Atlas for Taiwan. Fang explained, "In the 1990s, the TWBF proposed this project to map Taiwan's bird populations. The fundamentals were based on the database. It would divide Taiwan into 400 squares, and each one was a 10kmx10km grid. Some bird society members were very interested in it such as the well-known birder and member of Nantou Wild Bird Society Tsai Mu-chi. However, there were problems. The first was that the data was so refined it wasn't possible to put in our system. They needed to write a program to log in the data and it was tedious as there were so many points. The code-writing was handled by people from the Wild Bird Society of Hsinchu. They provided the program to input. This project was mainly overseen by Wei Mei-li, then-Secretary general of WBS Taipei and then-president of TWBF Guo Cheng-yu.”

Yet even with this support, execution of the project faced complications because of Taiwan's topography. As Dr. L. Severinghaus put it, "Taiwan is not flat. It is difficult terrain. You might be assigned a square that is impossible to get to or take so much time getting to, you couldn't finish in time." Due to these input issues and capacity problems, the atlas never came to fruition, but the effort nevertheless contributed significantly to data on Taiwan's birds.

Flying into the New Millennium (1999-2000)

In the words of former TWBF president Dr. Fang Woei-horng, "We experienced quite a lot of activity and made a lot of noise in the late 1990s and early 2000s. It would be hard to replicate that today." Indeed, this was one of the busiest periods of time for the TWBF as well as its partner organizations. By 1999, TWBF partner organizations were found all over Taiwan. Some of the smaller groups were mainly organizing birdwatching activities or doing education and outreach work. Others were involved in conservation work, such as the WBS Tainan, which had been working with TWBF and international groups on the conservation of the Black-faced Spoonbill. In 1999, their largest partner, the WBS Taipei, had a new idea to create Taiwan's largest birdwatching festival. One of the people involved would go on be the Taiwan Wild Bird Federation's longest serving secretary-general, Victor Yu. He served in the role from 2006-2011.

Yu said he became interested in birdwatching around 1991 while on a visit to Kaohsiung. When he returned to Taipei, he signed up with the WBS Taipei and took birdwatching lessons before moving on to become a volunteer. After retiring from work as a military instructor in the late 1990s, he began serving as the secretary-general of the WBS Taipei. It was in this role that he helped organize the first Taipei Birdwatching Fair. "Taiwan had migratory bird festivals before, and at that time the president of WBST, Guang Xin-ren, said we should do something bigger, and not just a fair but a festival. So we organized a committee and I was one of the key members of it.”

Trouble struck though when funds promised by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to welcome international participants were later withdrawn in response to a major earthquake that hit Taiwan on September 21, 1999. With no budget, some on the committee suggested canceling the event altogether. Others took a different tack. Yu was one of them. They thought of inviting diplomatic staff in Taiwan, contacting one after another and finding many participants to support the event. It went on to be a huge success. "We had a huge parade and the boy scouts held out the flag for each of the international members."

The first Guandu Bird Fair would see about 60,000 visitors (14).

After this, a group was formed to learn about international bird fairs, starting with the British Bird Fair, one of the oldest and biggest of its kind. Yu recalled, "We had our own ideas on how to do a bird fair. Taiwan was one of the first in region. Then there was the Philippine Bird Festival and the Thailand Bird Festival and Raptorwatch in Malaysia. We would do our best to support these efforts to celebrate the birds." The Taipei event would go on to be held annually and became today's Guandu International Birdwatching Fair, bringing tens of thousands of visitors over the years.

That same year, a small migratory passerine called the Fairy Pitta would again turn the attention of the bird conservation world to Taiwan. In 1999, rumor had it that a Fairy Pitta, a poorly understood species at the time, was breeding in the Pillow Hill area near Huben Village in western Taiwan's Yunlin County. This prompted the Wild Bird Society of Yunlin, a TWBF partner, to ask researcher Dr. Lin Ruey-Shing to help conduct a survey for the bird. Locals hoped to use the issue to stop a gravel extraction project from taking place in their area. After many Fairy Pittas were found breeding in the area, as little was known about the Fairy Pitta or its distribution, it was thought Taiwan might be home to the entire breeding population (6).

Fairy Pitta (Source: TWBF)

In February 2000, the TWBF launched a global appeal called "Save Huben Village – Home of the Fairy Pitta." By May, 73 international conservation organizations from 21 different countries had come out in support of the campaign, working with villagers to increase publicity for the issue and holding letter writing campaigns and petition drives (6). The TWBF applied to BirdLife International for IBA status for Pillow Mountain, which it received in September that year. Local efforts eventually led to a public hearing at the Legislative Yuan and a statement from Taiwan's then-President Chen Shui-bian. Meanwhile, on June 23, Taiwan's Council of Agriculture suspended gravel extraction operations and considered giving Huben and Pillow Hill the designation of "Major Wildlife Habitat." Marco Lambertini, then head of BirdLife International's International Affairs Division, came to Taiwan to talk to government officials on behalf of Huben (6).

The habitat was later threatened again by a dam for the Hushan Reservoir. Again, TWBF reached out to international partners for help. Two years later, in June 2006, BirdLife International sent Jonathan Eames, International Programme Manager for Indochina, and Richard Grimmett, Birdlife Asia Division Head, to participate in the first International Fairy Pitta Symposium hosted by the National Coalition Against the Hushan Dam in 2006 (6). Grimmett spoke at the meeting about the need for a coordinated effort by organizations across the Fairy Pitta's range in Japan, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Borneo to work together to protect the bird's habitat. Dr. Lin’s work also showed that the species was not confined to Huben but also bred in many parts of Taiwan. Further research abroad would also show that it bred in other countries such as Korea, Japan, and China. Though the dam eventually was built, the issue galvanized a generation of Taiwanese conservationists.

By 2000, the ornithological community had grown, with a number of organizations, researchers, and even university labs working on topics related to birds and their conservation. Many of the TWBF's partners were now also better established and taking on new responsibilities in the conservation community. For instance, the Kaohsiung Wild Bird Society formally started to manage the Niaosong Wetland Park, Taiwan’s first wetland park (4). Also, in order to help protect Taiwan's dwindling Pheasant-tailed Jacana population, the TWBF along with wetland conservation group Wetlands Taiwan and others helped found the Pheasant-tailed Jacana Rehabilitation Area in southern Tainan City's Guantian District. The 15 ha site was considered the last bastion of the population which was only around 50 (11). The area is Taiwan's water chestnut capital, and the jacanas use the floating leaves to build their nests and feed on bugs. It was first managed by the Kaohsiung Wild Bird Society. This role would later be taken by the Wild Bird Society of Tainan.

Meanwhile, the biggest conservation story of that year was the rediscovery of the "Mythical Bird," the Chinese Crested Tern, in Taiwan (8). The rediscovery was made in the Matsu archipelago, a group of islands controlled by Taiwan that lie just off the coast of China. For almost 50 years, the small archipelago served as a military outpost with restricted access to all but military personnel and local residents. Then, in the mid-1990s, as tensions cooled across the Taiwan Strait, the islands were opened to the public. Birdwatchers jumped at this chance as Matsu hosts a number of seabirds, particularly birds from mainland Asia that can't be seen in Taiwan. It was at that time that the TWBF applied to conduct surveys of Matsu's 36 islands to learn more about the wildlife situation there (8). It was known that large numbers of seabirds were using some of the uninhabited rocky islands for breeding. Thanks to the surveys, eight islands were later declared as the Matsu Island Tern Refuge in 2000. Many local people were still fishing and harvesting seafood in the area at that time, so the TWBF hired director C.T. Liang to create a documentary to raise awareness about islet ecosystems and their importance. In the end, it was Liang who first noticed that some of the Greater Crested Terns (GCT) seemed different.

A Chinese Crested Tern (center) with Greater Crested Terns on either side (Source TWBF)

Liang sent his footage to the TWBF, which confirmed that the birds captured on video were in fact different. With a total of eight adults and two chicks recorded, the status of the CCT was revised from presumed extinct to critically endangered, and its population was assessed at around 50 individuals. At that point, nobody knew how many there were, but scientists and conservationists wanted to find out. Soon after the discovery in Taiwan, another breeding group was spotted in China's Zhoushan Islands off the coast of Zhejiang Province. In 2002, the bird was listed as an Appendix 1 species in the United Nations Environmental Programme Convention on Migratory Species. The inclusion marked a big step forward in CCT conservation work as it highlighted the risk of extinction in some or all of its range and advised that it should therefore be protected by all countries in which it appeared. Though initial work mainly involved the TWBF, it later shifted to a collaboration between the Wild Bird Society of Taipei and the Wild Bird Society of Matsu along with Prof. Yuan Xiao-wei of National Taiwan University. In 2006, a major meeting took place with Prof. Yuan of Taiwan, Dr. Chen Shui-hua of China and Simba Chan of BirdLife International Asia Division. This meeting subsequently led to the inception of the International Single Species Action Plan for the Conservation of the Chinese Crested Tern (8). The TWBF continued to help and lend support in the form of international outreach, communication aid, and management of a rodent removal project for one of the refuge islands in 2008.

The year 2000 also saw the launch of a collaboration between BirdLife International and the TWBF called E-Birds: Promote the Global Protection of Wild Bird Series. With a theme of "Save the Birds—Save the Trees—Save the Earth," it looked to raise awareness of the threats to bird species and bring together like-minded groups and individuals from across the globe. Via the support of Taiwan's Council of Agriculture and other central and local government agencies, Taiwan, the TWBF, and its partners hosted a number of student competitions locally and internationally based around the theme of birds and conservation. For the international competition, each region of the BirdLife partnership was awarded winning submissions, with winning entrants given the opportunity to come to Taiwan for an award ceremony held in November 2001. At the event, keynote speeches were made by Baroness Barbara Young of Old Scone and BirdLife International Director-General and CEO Dr. Michael Rands. At the end of the event, Rand delivered a presentation on the State of the World's Birds and Strategy for BirdLife International (12).

The International E-Birds Awards Ceremony & Conservation Conference event booklet (Source: TWBF Archives)

Part 3 will look at how the TWBF matured and changed in the early 2000s and embraced the age of citizen science.

Part 1: A Historical Review of Ornithological Study and Birdwatching Groups in Taiwan

References:

(1) Chinese Wild Bird Federation. 1996. Zhonghua Fei Yu 2nd Quarterly. 中華飛羽 Vol. 2 No. 2. Cover (中文) Retrieved 8/23/2023

https://www.bird.org.tw/sites/default/files/field/file/download/2%E6%9C%9F%E5%AD%A3%E5%88%8A-199604.pdf?fbclid=IwAR2VOhYmDrDK4RIyxwOG7smfIZX8C0FQymby7x5BV-nlO-B4qx2mV-xU8Ko

(2) Forestry Bureau, Council of Agriculture, Executive Yuan, ROC (Taiwan), Chinese Wild Bird Federation. 2015. Important Bird Areas in Taiwan. Taipei, Taiwan.

(3) Hsieh, CK. 2017. The Shaping and Promotion of Ornithology and Birdwatching in Taiwan (1945-1989), [Doctoral Dissertation National Chengchi University]. National Chengchi University Electronic Theses and Dissertations (中文)

http://thesis.lib.nccu.edu.tw/cgi-bin/gs32/gsweb.cgi?o=dallcdr&s=id=%22G0102158017%22.&searchmode=basic(link is external)

(4) Kaohsiung Wild Bird Society. 2016. A Brief Introduction to Niaosong Wetland Park. Retrieved 8/1/2023

https://www.kwbs.org.tw/wetland/english/Brief_introduction.html

(5) Lin, WH. 1997. The Discovery of the Birds of Taiwan. Yushan Press. Taipei, Taiwan. (中文)

(6) Pursner, S. 2022. Eight Colors, One Future: Fairy Pitta Conservation in Taiwan and Efforts for the Future-Part 1. Taiwan Wild Bird Federation. Retrieved 8/1/2023

https://www.bird.org.tw/publish/2228

(7) Pursner, S. 2021. Let's Get Hei-Pi: A Review of Black-faced Spoonbill Conservation Efforts in Taiwan - Part 1. Taiwan Wild Bird Federation. Retrieved 8/1/2023

https://www.bird.org.tw/publish/1201

(8) Pursner, S. 2020. Return of the Mythical Bird: Conservation Efforts to save the Chinese Crested Tern in Taiwan. Taiwan Wild Bird Federation. Retrieved 8/1/2023

https://www.bird.org.tw/publish/407

(9) Severinghaus LL, Ding TS, Fang WH, 4 Lin WH, Tsai MC, Yen CW. 2017. The Avifauna of Taiwan. Vol. 2. Forestry Bureau, Council of Agriculture, Taipei, Taiwan.

(10) Taiwan Biodiversity Research Institute. 2023. Foreword. Retrieved 8/1/2023

https://www.tbri.gov.tw/en

(11) Taiwan Wild Bird Federation. 2021. A Case Study in Community Conservation: Reviving a Pheasant-tailed Jacana Population by Ensuring the Survival of the Socio-Economic Landscape in Guantian, Tainan, Taiwan. International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative. Retrieved 8/1/2023

https://satoyama-initiative.org/case_studies/a-case-study-in-community-conservation-reviving-a-pheasant-tailed-jacana-population-by-ensuring-the-survival-of-the-socio-economic-landscape-in-guantian-tainan-taiwan/

(12) Wild Bird Federation Taiwan, BirdLife International, National Taiwan Science Education Center. 11/2/2001. International E-Birds Awards Ceremony & Conservation Conference. TWBF Archive

(13) Wild Bird Society of the ROC. 1995. Checklist of the birds of Taiwan. 中華飛羽 82(6):22-32. (中文) Retrieved 6/8/2023

https://www.bird.org.tw/sites/default/files/field/file/download/%E4%B8%AD%E8%8F%AF%E9%A3%9B%E7%BE%BD82%E6%9C%9F-1995-6-%E9%81%AE.pdf

(14) Wild Bird Society of Taipei. 7/22/2014. The Story of Yuhina Over Four decades [Video]. YouTube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yg6KwjTD7F0